Housing is an important topic for all small housing providers. Whenever there’s a publication on this issue, we’re interested in the perspectives and ideas offered. Today, I’m going to take a closer look at Ricardo Tranjan’s book, The Tenant Class which was released on May 2, 2023.

The core thesis for Tranjan is that “There is no ‘housing crisis’ just good old landlords squeezing high rents from tenants” in this and many regards, the book is displaced from the everyday reality for both landlords and tenants. In fact, Tranjan launches into his faux-provocative prose almost immediately. In fact, by page two he says, “More importantly, the problem with all this crisis talk is that there is no actual ‘housing crisis.’” You read that correctly, this book is about to explain why all these people talking about a “housing crisis” are just full of hooey.

I could get with him on some of these points, but by page 4, Tranjan is already spouting falsehoods. He said, “The COVID-19 pandemic became an opportunity for landlords to evict tenants, who fell into arrears due to the economic shutdown, and hike up rents.” Well, our members at that moment might be different, but first off, the Landlord and Tenant Board in Ontario instituted a moratorium on evictions from March to August of 2020, meaning those who didn’t pay rent could not be evicted. On top of that, Doug Ford was encouraging people not to pay rent. Given a climate like this, there was a rise of groups saying, “Keep your rent.” Put together, there were likely few small rental operators in Ontario evicting or “hiking rents” during COVID-19. But, just about every one of those housing providers faced serious difficulty as rental income dried up.

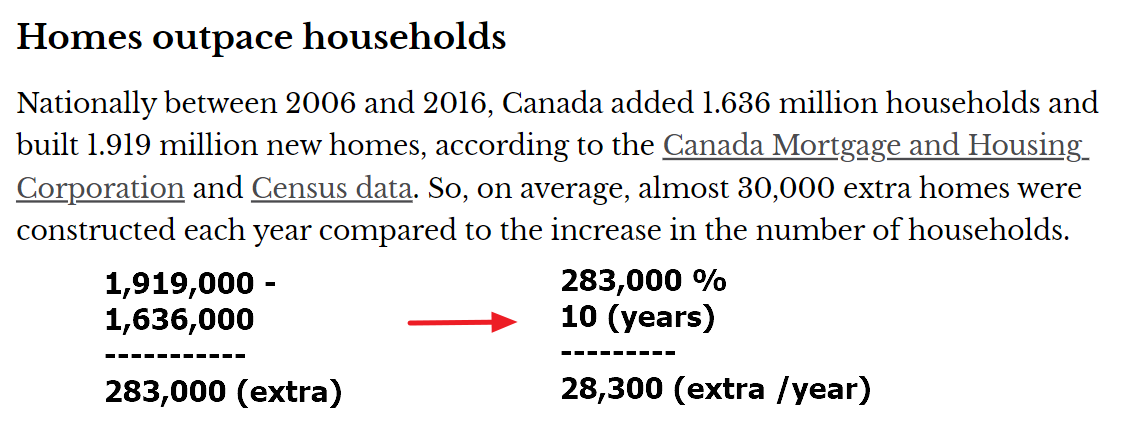

One of Tranjan’s key points (on page 7) for why the crisis is imaginary is that Canada added “30,000” net homes (of two million added) in a ten-year timespan – to say that supply increased – and yet prices still went up. If you’re scratching your head at that low number, there’s a reason. It’s a typo (see update below). He likely means to say, “almost 300,000 homes.” This kind of typo is fine somewhere else, but as we landlords know too well, something like this would be a fatal error at the LTB on a termination notice.

Update: Ricardo reached out about my number correction in his book, which as I was reading, seemed off. I went back to the book, then back to his source and he was right, this is an error on my part. The almost 30,000 homes is a number related as extra and per year. Correctness matters and I’m all to happy to make this correction. Thanks to him for pointing this out.

The source looks like this:

Back to the book, his message also depends on the tenant being an underclass. He even says it: “Canadian society treats tenants like an inferior group.” But I don’t think this is the case. In 2013 Ontario, tenants are afforded so much power that they can quite literally exploit a landlord to death. Is that someone treated like an inferior group? Tenants, in fact span all classes. Many SOLO members are tenants and landlords. And, because the allure of home ownership has shifted with the high cost of real estate and, well, generational tastes. It’s not the aspiration it was when I was growing up in 1980s Toronto. Contrast that with Tranjan, who hails from 1980s São Paulo, Brazil. Tranjan explains that he comes from a time of unrest. Brazil of the 1980s was becoming a violent hub for illicit drugs. The military and police used extreme force often. As Tranjan describes it: “the end tail of the military regime.”

Tranjan often uses the phrase “landlords extract profits.” But there is nowhere in this book that breaks down that very profit he argues against. His argument seems to depend on the fact that being a housing provider automatically generates high profits and that we all just accept it. The reality for a small landlord is disenfranchisement where tenants have enormous legal power and leeway, yet small landlords are still treated like large, greedy entities that likely staff paralegals. The slow and bumbling, bureaucratic LTB makes quick work of the immigrant homeowner if they make an attempt to self-represent and navigate the morass of LTB forms and procedures. To watch it unfold day after day is a tragedy.

He suggests that rents increased higher than inflation and incomes all over the country. This is well known, but since when did the market rise to the tune of only inflation? What market is artificially pegged to income? Do you think gas increases are pegged to household income? I’m not sure Tranjan is out so solve why incomes have been stagnant in modern times, so mentioning these things seems out of place.

His four tenant myths – renting is a phase people grow out of, tenants don’t pay property tax, a large share of tenants don’t work, and anyone would try anything to own a home are just generally wrong, but more than that, not something you’d consider widespread by any measure. That they’re all prejudicial ideas to hold about tenants, yes, sure. But really, a tenant pays rent and there are people who think the payment wouldn’t go towards property taxes? And, “tenants don’t work” is a myth? It’s absurd to suggest that “most” people think tenants don’t have jobs. Are there any people out there that think a tenant carrying $3,000 a month rental is not gainfully working? These myths are either lazy or just absurd.

“When we remove profit from rental housing, rents drop” – there are so many misconceptions at work here. Both public and private housing costs money. Given that, removing the profit means making rental housing a massive loss to governments. Eventually, while social housing decays, the public stops supporting the high cost for tax money. In social housing, there is little incentive to improve and upgrade. This leads to overall disrepair as years pass. The suggestion by him that public housing is as safe and good as private housing, has Tranjan ever been to the former Regent Park or any other now-neglected public housing project?

On page 46 Tranjan makes the bizarre point that “tenants don’t choose to fall into arrears.” For many landlords, we’ve learned that this is demonstrably false. With the climate created by a pandemic, political nudging from many directions saying “keep your rent” with failing justice systems and levels-deep bureaucracy, there are too many tenants that have just decided to stop paying rent. This action is actually contagious as SOLO members have seen tenants in duplexes see others stop rent downstairs, then following suit. One unintended problem caused by all this is that tenants fall so far behind, that they can’t get back on track. How laughable is all this? On page 69 Tranjan describes an historic case where, in 1864, Prince Edward Island tenants actually organized and chose to withhold rent. Which is it then? Tenants chose to not pay rent in P.E.I., but somehow don’t chose to when it’s convenient? Tranjan appears to think it’s good to steal rent as long as the cause appears righteous to him. By page 83, a “rent strike” is glowingly presented as fighting the power, not choosing to fall into arrears. Rather conveniently, the wording used is “strike” or “withholding,” never the truth: choosing to not pay rent and fall into arrears.

It’s early in the book, but my distinct sense is that Tranjan wishes to do away with private property interests altogether. Has he considered what would happen to taxation if the government took over all housing? Has he considered the challenges of mixing income levels in complexes? Has he considered the poor maintenance outcomes that exist from bureaucratic wrangling in Government housing today? In this book, it doesn’t seem so.

Tranjan also takes issue with “small-time” or “mom and pop landlords” – he trumpets the same line we often hear about bad investments face risk – like on page 46 “a private investor looked for a low-risk investment with high returns.. [But saw] operational losses.” Tranjan doesn’t seem to see anyone but the “house flipper,” he can’t imagine the immigrant buying a house and renting that house only to rent in a new location for practicality. He can’t imagine two homeowners coming together to marry, only to own homes between them and renting. The reality of small landlords is as varied as the journey that got them to home ownership in the first place.

Tranjan also takes issue with the characterizing of landlords as “mom and pop.” He calls this a ”central plank in the depoliticizing of housing.” His point is that, by making housing a technical problem to solve, it takes away from the need for tenants to politically organize. That would be fine if he knew what “mom and pop” landlords were. He doesn’t. By page 47, Tranjan barely admits the small landlord exists but it’s a small fraction of them. He says, “Popular culture and the media greatly exaggerate the share of landlords in this ‘struggling-to-pay-their-own-mortgage category.’”

His thin source for this stat? “Statistics Canada that cites four percent of homeowners in Canada rent a portion of their house.” Despite this not covering a reasonable definition of what a small landlord is, Statics Canada has no statistic that accurately describes the small landlord population (homeowners with six or less rental units, let’s say). Tranjan shows continually that he doesn’t understand small landlords. By page 49 he’s describing “mom and pop” landlords as owning 44 units on average. He really doesn’t know what he’s talking about. He uses these terms to suit his needs, but never cedes to the existence of a struggling small housing provider. At SOLO, we’re supporting many thousands of them and these ranks are growing.

It feels very ironic that Tranjan would seemingly defend the working-class or tenant class, when the small landlord is exactly the type of working-class group he should also be defending. This manifesto hangs them out to dry. If home ownership is here to stay – it is, and small landlords will continue to exist – they will, we need to be fighting for fairness, appropriate incentives and more power to working-class folks trying to get ahead (in any way they want to). It shouldn’t be such a crime to be a small rental operator. Indeed, Tranjan states he’d “do away” with any small landlord that doesn’t live up to his standards in the ludicrously bad Ontario market.

One thing is for sure, for every small landlord that is lost to the market, either the supply of rental units drops or, even worse, a large Real Estate investment Trust does what Tranjan warns us about. Both are bad outcomes, crisis or no crisis. Tranjan’s efforts seem best suited to ending capitalism, not ending the livelihoods of small landlords. For him, perhaps that’s a worthy goal, but the rest of us struggling in the Ontario market should stop falling for this kind of antagonistic rhetoric and finds ways to work together. An end to private housing is an earthquake-level shift.

The chapter on past tenant organizing groups is a good read and worth following. All over the country, tenants have gotten together to fight unfair conditions and have won the day in many cases. Tenant organizing is not at odds with small landlords, it is at odds with large corporations.

Tranjan’s 10 minute interview with Steve Paikin offered him the opportunity to repeat many of the things he says in the book.

“Well, investors had some money set aside, they decided to go for something that is high returns and low risk, so they went into the real estate market. What happened is that business didn’t go as they desired, they had some operation losses but they still had capital gains that more than offset their operational losses.”

Again, he picks up on this myth that small landlords are just investors that have an easy to-to-recover loss. When the average small landlord could lose $35,000 or more in rent arrears and even more in damages with a bad tenant, this is not something a small housing provider can take and still keep their homes.

What we’re seeing at SOLO is the rise of a group of landlords that, by way of circumstance, the shifting economy or other issues that own few properties, and are doing what they can to stay owners, stay housed and house others in the riskiest Canadian rental market: Ontario. When will Tranjan write the book The Small Landlord Class?

The apt final chapter is entitled “Pick a side.” Throughout this short book’s 110 pages, Tranjan has put forward an us-versus-them view that, frankly, threatens to throw away progress. Tenants should have safe and properly maintained homes. They should not be harassed. For all of us, no matter if we’re a tenant, housing provider or other, we should be able to live somewhere we can make a home. SOLO Ontario supports good tenants as much as we support for good landlords. When we’re all fighting, we’re all losing.

SOLO has been advocating for small housing providers for a number of years. Our thousands of members face the destruction of their financial lives due to a lack of justice and systemic issues they cannot solve alone. If you are a rental operator or homeowner, we welcome you to join in this fight to improve housing for all.